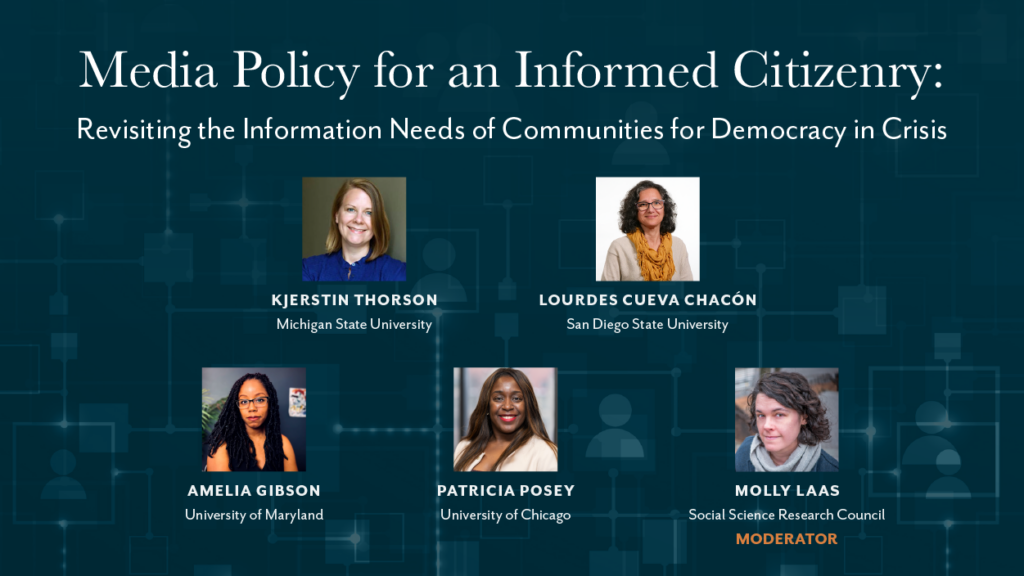

Last month, the AAPSS partnered with the Social Science Research Council for a webinar covering insights and findings from the recent volume of The ANNALS: Media Policy for an Informed Citizenry: Revisiting the Information Needs of Communities for Democracy in Crisis. Moderated by Molly Laas, the panel of experts—Lourdes Cueva Chacón, Amelia Gibson, Patricia Posey, and Kjerstin Thorson—shared their thoughts on the crisis for communities whose information needs are no longer being met by local journalism.

An edited transcript of this webinar is below, and links to the articles discussed are provided at the end of the post.

Molly Laas: Hello everyone, I am Molly Laas. I’m the program director of the Media and Democracy Program at the Social Science Research Council, and I’m really pleased to welcome you to our webinar today on Media Policy for an Informed Citizenry: Revisiting the Information Needs of Communities for Democracy in Crisis. In the past two decades, the centrality of the internet and social media in the news and information environment has changed the economics of journalism and dramatically reconfigured how and where citizens obtained news and information. A crisis in journalism has engendered a crisis of information needs. It has become more difficult for citizens to effectively learn what they need to know to be well-informed participants in the democratic process.

In this webinar, we have four experts to lay out the stakes for communities whose traditional sources of reliable community information, such as local newspapers, have been disrupted by both digital platforms and the changing economics of local journalism. So, we have with us today Lourdes Cueva Chacón, Amelia Gibson, Patricia Posey, and Kjerstin Thorson, and they’re here to discuss these questions, which are particularly critical ones for communities of color and lower income communities, exacerbated by local news sources’ longstanding tendency to produce content that fails to meet these communities’ needs.

This work comes out of a new special issue of The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, which is edited by Nikki Usher, Josh Darr, Philip Napoli, and Michael Miller, and this work came out of a workshop that was sponsored by the Social Science Research Council. This really great special issue provides a snapshot of the current state of knowledge and explores possible policy interventions for maintaining news and information ecosystems that effectively serve the information needs of communities in a democracy.

I’d like for the panelists, please, to introduce themselves before we begin our conversation. So, Lourdes, if you’d like to lead us off.

Lourdes Cueva Chacón: I’m happy to be here. My name is Lourdes Cueva Chacón. I’m an assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Media Studies at San Diego State University, and I focus my research on Spanish-language and Latinx media in the U.S.

Amelia Gibson: My name is Amelia Gibson, and I am an associate professor at the College of Information Studies at the University of Maryland at College Park. And I study information access, marginalization, and safety in public institutions and libraries, health care, and education.

Patricia Posey: Hi, I’m Patricia Posey. I’m an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, in political science. Broadly, I examine the relationship between race and the American political economy, focusing on the link between space and political behavior. In some ways, you can say I focus on questions of the politics of everyday life.

Kjerstin Thorson: Hi everyone, I’m Kjerstin Thorson. I’m a professor of political communication at Michigan State University. With my research team over the past few years, we’ve been studying what might happen if we hand over local civic information infrastructure to digital platforms of various kinds. So, I’m very interested in investigating the question of what might come after local news. What will we see more of, and what might we see less of?

Laas: Great, thank you. So, I would like to set the stage here by providing a grounding question, which is: Why do we each care if communities have information? Lourdes, if you want to start off.

Cueva Chacón: Sure. Since I focus on Spanish-language and Latinx media, I’m going to talk more about that. And so, why we care about them having information is because then they will be able to join the larger communities they are part of and become productive citizens, more informed citizens, and more participative in the larger decision-making [process] in their communities. They will improve their quality of life, and they will be able to raise bilingual citizens. They will be citizens that are going to contribute to our larger society in the U.S. And so, by giving them the information they need, they will be able to grow and flourish, which is why we’re here to help develop that.

Gibson: I’m gonna follow up a little bit. So, for me, kind of going off with what Lourdes says, information systems—information in communities—is essentially about citizenship to some degree, right? Our access to citizenship in this country, if we think about the ways we talk about democracy and participation—a lot of that is based on good information, right?

Information systems and services structure the boundaries of what’s possible for communities and people in our country, to some degree. Along with other things, clearly, this is economic. But they will often work in ways that aren’t immediately obvious to people who are interacting with those systems. They’re often very hidden and they comprise this systemic discrimination, etc., that we talk about in other domains and other fields. And so, if we’re able to understand how those systems work, we could also look at the ways that they disincentivize certain use or certain sharing [of] information that we might think of as good otherwise.

In some of the work that I’m doing now, we look at social determinants of health data and how much good that could do for folks providing care and mitigating systemic discrimination or disparities, health disparities. But just interacting with those systems—social systems, health care systems—also has its own dangers for people who might face things like family separation, etc., by giving away this kind of information. So, for me, information and community are interesting or important, because we need to understand how people make those choices when we’re setting up Faustian bargains that make people choose between one dangerous choice and another.

Posey: The media landscape has changed, and it’s becoming increasingly fast and cheap. And there’s all these ways to consume information, but access to that information is highly unequal. And, as noted, these questions have such large ties, questions of lived experiences, and kind of notions of citizenship: from my perspective, racial and economic inequality readily translates into information disparities. Many racially and economically marginalized communities live in information environments that fail to provide in-depth coverage of critical topics such as day-to-day finances.

When I think about why I care about whether communities have information, I think about the fact that both financial institutions and news providers have historically underserved racially and economically marginalized communities, and this contributes to information gaps in both financial news and creates the need for these alternative sources. And some consequences of this is that you end up having limited access to financial news and information, especially about personal finances. You end up creating an environment where the importance of lived experiences is essential in this kind of informal information economy where folks need to provide community level information through non-traditional, often neglected sources in the neighborhood—such as sharing your experiences in a physical storefront or as you’re walking down the street.

And then finally, you know, these notions of inequity in this information means that the consequences that Amelia ended by talking about, these questions of citizenship and kind of lived experiences and how people are kind of trading off between detrimental sources, become even more dire.

Thorson: So, on my end, first of all, we know from quite a bit of research that better things happen in communities well served with actual local information, whether that’s things like voting turnout or more sort of perceptual variables, like community resilience or community identity or that sort of sense of belonging. Capacity to think of ourselves as acting together around a particular issue or even levels of polarization. And one of the wonderful tidbits—and there’s quite a bit in the ANNALS volume on this topic, but one of the wonderful tidbits that’s mentioned—is that unfortunately, as more and more local news organizations disappear, it’s given us more opportunities to study this horrific question of what happens when we rip local news out of that community ecosystem.

So, my take on it is, first of all, it has never been the case that communities were fully informed, and I think that’s not really the place that we start. Of course, there have always been people who either didn’t pay attention or were excluded in various ways from representation and so didn’t use these kinds of outlets and forums. However, despite that, the vision of information and the capacity for a community to produce enough information so that its citizens can be informed when they need to be or in cases of crisis or in cases of urgency remains incredibly important.

And the second reason, to me, is that because we got so used to over the past sort of 50 or 60 years talking about community information and journalism as the same thing, we missed a lot of stuff that was happening. Each one of my previous co-presenters has mentioned this in various ways. We really missed a lot about the information provisions and creations that were happening outside of that ecosystem, because it was easier to pay attention to this one central hub for content.

Well, as local news goes away, suddenly there are these questions of, “if not journalism, then what?” This has become really, really urgent. And I think that’s what’s interesting for me: what that information or content is, where people will find out, what kinds of voices get surfaced, and what kinds don’t—when we’ve lost that sort of keystone piece of it that we’ve gotten really used to.

Laas: Great, thank you. So, I’m glad you ended on that, Kjerstin, because we’re interested to talk more about journalism. Where does journalism fit into community information needs? And if journalism isn’t meeting people’s needs, who else is providing information?

Cueva Chacón: What I believe is that journalists are trained to kind of have a bigger picture, right? They can discern what is best for the communities. The problem, I think, has been when losing local news, the disconnection or the time that the journalists have had before to be more connected with their communities has been lost. And so, we’re seeing more coverage of national news even in a Spanish language, like when you see Univision and Telemundo—which are the providers of news in Spanish—going and behaving the same as mainstream media and losing that connection with smaller communities.

Even though we call them “ethnic media,” I think they have fulfilled certain roles such as being the ambassadors, the mediators, the translators for their communities. This connection is becoming larger and larger, and so I think, and as I show in my study and my contribution to the volume, it’s highly trained journalists who are talking and listening—especially listening—to the communities. They want to serve. They are the ones who are regaining this trust and providing back the information that the communities need.

And after doing that work, they can also report beyond those communities. Power brokers, local government, state government understand what’s happening with these communities and then can build on that information to create policies or to make policies that help the development of the overall communities. And so, I do think journalists fit in these environments; it’s just the need to listen closer to what the communities need. Sometimes it’s daily issues such as, you know, paying rent, getting help when there’s flooding, things like that. But it’s important information that the communities need, or individuals need, to go on with their daily lives and then relieve some of the stress of those problems, that are going to allow them a space to think more about larger issues and to give them that space and that confidence so they can participate as well.

And I think that’s very important. And the other thing is that journalists who listen, they can understand—as the people in my research showed—that sometimes what we as scholars are looking at is that the larger U.S.’s information needs are not necessarily the same as the information needs in other communities. Look at people who live closer to the borders: they are mostly Spanish speakers, and so those information needs are a little bit different. So, I think that’s where journalists fit. Also, you can see that when we have to talk about these structural issues, it’s journalists who actually are more or better trained to talk about these racial and structural problems. Then, sometimes, organizations within the communities don’t necessarily have that larger knowledge, or they are maybe afraid. I’d better let Kjerstin talk more about that.

Thorson: Thanks. That’s such a great point, and I love the way you’re sort of surfacing this idea that different organizations are good at different stuff within their communities. I have thought of my own research career as sort of marked by a sense of optimism that sure, you know, media environments change. They have always changed, and then we figure something out and it works out. And so, when we started researching sort of what might come after local news, I was really optimistic to think about sort of the rich breadth and networks of civic organizations in communities, whether that’s nonprofits or local governments—not just politicians, but the institutionalized functions of local governments.

Libraries are these incredible content creators and many other places within our local communities. I really thought we would see that those organizations would take the rise of digital platforms as an opportunity to, I don’t know, be stronger voices or make stronger contributions to informing local communities. But, as Lourdes points out, oftentimes those organizations are very poorly equipped to be those kinds of communicators, and that’s especially the case for issues and topics that are that are difficult for people to talk about or that produce controversy.

So, what we find is that it is really only—or primarily, but pretty much only—local news organizations that are willing to tackle topics, like, let’s talk about the political issues in a community because they are resilient to disagreement. It’s usual for people to disagree or argue with news organizations, and we have all sorts of norms and practices to sort of deal and manage with that. On the other hand, if you run a nonprofit that’s deeply passionate about an equity issue in your own community, and you post on Facebook a long thoughtful, detailed, reasoned—maybe even quite journalistic—post about how much that issue matters to your constituents, you’re then jumped or piled on by all sorts of people in the comments and in spaces that create difficulty and a sense of toxicity around your own information environment.

So, for me, what journalism is still really, really good at and really, really important [for] is tackling topics—not only, you know, listening and attending to what communities need, but then also finding ways to bring forward really, really important, complex issues that may be hard for people and local communities to talk about.

Laas: Thank you. My next question is about mis and disinformation and I’m interested to think about our framing of centering community information needs and how that might change how we understand mis and disinformation. So, Amelia, if you’d like to let us know.

Gibson: Sure. I think I wanna start maybe from where Kjerstin left off. The last question was about where, other than sort of traditional news journalism, people find information. And I think, when you’re thinking from the community perspective, a lot of people don’t think about information like journalism as separate from the sort of more organic information sources that they use or as part of a flow of information, right?

So, when we study community information, most people respond that the Google answer box is where they find most of their health information, especially if we’re talking about things like COVID, right? Google’s answer box was the thing that popped up and told you what the rate in your state was. Not even your local area for some places, just your state. And so, there was this sort of sense of local relevance to national [COVID] news, but only so much as they could isolate it through a constellation of other local information sources.

Another source was local school systems. For people who had children, perspective on what was going on during the height of the pandemic was, like it was for a lot of people, shaped by the discussions about school closure or opening. Those were infection percentage rates; a lot of schools were looking at those kinds of things. When you talk about that local information landscape and how journalism, on more of a national level, fits in with that information landscape, that’s where people found conflicts that, I think, informed the way we think about information, misinformation, and disinformation, especially about health.

So, I’ll say people respond fairly predictably to like information systems that don’t give them good options or don’t give them good information. Often they’ll opt out if they can, engage in practices like secrecy, silence. They’ll build on—I think Patricia mentioned this—building your own sources of information. With lateral information sharing, sometimes that information is “good”—or what we call good. For those of us who study information literacy, there’s definitely good behavior, good practices and bad practices. And sometimes they’re not so good. And we talk about reasonable responses and decision making based on information. But the thing that became clear to me, as I talked to people about the way they made decisions based on the COVID information in their local information environments and information ecosystem, was that they judged the national news according to the local news and not [the] opposite. So, what I found was that if the national news said we should be wearing masks now, they would decide on whether or not that was trustworthy or relevant based on what they saw in their own communities.

The local becomes more important, but then also folks who are in these subcommunities find themselves in another like no-win situation. So, if you’re a person, for example, who has an invisible developmental disability such as being autistic, you have something going on that people don’t know about in your everyday life, right? In pre-COVID times, that was not necessarily something you had to deal with at your job. That isn’t something you might have had to engage in with other people. It didn’t inform a lot of the decisions that you made around health. But when we got into COVID and people were making decisions or talking about risk based on what they assumed most people had or most people do or most people are, you’d find yourself suddenly in a group of people for whom that “good” source of information—those good information practices—is no longer relevant. So, you’re in this state of conflict now: you have this standard for health literacy—what is normal, what is good, what is appropriate—and then, because you’re in this group that is not the “norm,” none of that is relevant to you. I found that that kind of called into question a lot of the ways that we talked of this information during COVID. Questions like “what is useful information?” and “what is good information?” were often predicated around belonging to these groups that were low risk or had clear or obvious risks. And most people were not in those groups.

Cueva Chacón: If I can follow up on that, Molly, the thing that I like about the study that I did was that news organizations were created or joined by journalists or bilingual journalists who realized that the people were getting their news from other places. Some of the places that they would meet would be WhatsApp or SMS or other internet mobile systems or services or applications, right? And so, what they decided was then that they had to go there; they said, “we have to go to those places and distribute information among them wherever they are.”

And I think that’s again another contribution of journalism. It’s a change: it’s not—we’re not—waiting for policymakers, power brokers, or other people or organizations to send us their press releases so we can build news based on that. There are groups of people and there are communities that are meeting already online, and [journalists] are distributing information in those spaces. But they’re receiving misinformation in these digital spaces, and so what we want to do is to go meet them where they are. That way they could ask “what is it that you need?” or “what is it that you’re hearing?” and then we can clarify the information that they have, whatever they are using. We’re getting it from the same places and in the same spaces where they are, right?

So, I think that is very valuable. I just want to mention the big foundation that is funding local news [Press Forward] has actually started funding some of these organizations I was researching. [Local news is] now on the horizon of these big funders, because they are realizing the contributions they’re making. In the past two years since I started my research, their audience has duplicated or grown like fivefold. They reach many more people through different channels.

Laas: Thank you, Lourdes. So, to think about more of a case study approach, I’m interested to think about what happens when a single platform, say for example Facebook, centralizes the issues that are being talked about by local community organizations.

Thorson: So, one of the clear things that we’ve been finding over several cases—in the article that we have in The ANNALS, we look at six different cities, but we looked at some other cities previous to that—is that increasingly Facebook has become sort of a hub. It is the place where many people go to try to find out information about what’s happening in their communities—as well, of course, as Google—but also increasingly, therefore, where other organizations go to provide information or to try to connect with people through Facebook as this core intermediary.

And so, this question of what happens when we do that, I think, is a really interesting one. And the reason is because every sort of hub or central actor in any information ecosystem brings its own baggage with it. Certainly, local news brought a lot of baggage in terms of what it was good at doing and what it’s always been not so good at doing, but a platform like Facebook brings all the Facebook-amplification baggage with it to the way people find out about their local communities. One way that we look at that is by looking across large volumes of Facebook data itself to see what people are posting. And then we sit down and talk to the people who are creating that kind of content and say, “why did you post this and not this? Why is this here and not that?” And we’re trying to make sense of that over space and time. What we find is that a lot of the things that we all know about Facebook—for example, that it’s often quite a toxic place to try to talk about anything complex in part because, you know, your Uncle Frank is there, as well as that person down the street who’s always got to be saying something about something—come into play now, quite visibly, in shaping the kinds of content that people are willing to produce.

We’re doing a study right now looking at volunteer moderators of local Facebook groups and Nextdoor groups. These are another critical and understudied source where people go to find out what’s happening in the world, and oftentimes, I use these groups not just to find out, you know, what’s happening in terms of important civic things, but also questions like “When can I plant my garden here in Michigan?” or “What’s a good restaurant to try for my kid’s birthday?” And those places also are sort of subject to the sort of toxicity of discourse; that is, they lend themselves to people coming on engaging in scams and propagating or simply engaging in discourse that isn’t maybe the way we want to talk about some of our civic lives in various ways. And so, I think we need to really think about how each of these platforms shapes how we learn about our communities, so that we are ready for what comes after Facebook.

I mean, the one thing I think we absolutely know is that it’s not just that the media system has changed, but that it’s always going to be changing from now on. It’ll be quite dynamic. So, what do we need to know about each one of these platforms as places for people to learn about their communities that may differ, for good and for bad, from systems and platforms that came before?

Gibson: Okay, Kjerstin—as you were talking about Facebook, what I was thinking about was when I was in the community. This is not like my research, so I have a question for you.

Thorson: Yeah.

Gibson: I was in a community where there was a discussion that happened on every school board meeting. It was a time. It was like everyone watched the meetings online because they were being broadcast online for the first time. And people would comment, and it was clear from discussions that were happening in the school board that there were people in the meeting on their Twitter, reading what was going on.

Thorson: Okay.

Gibson: So, things that would come up on Twitter would then be laced into things that people talked about as they were engaging in the meeting. Simultaneously, there was a very different type of discussion going on in the close like membership, local, school parents’ group, and you saw less of that sort of feeding into the meeting itself. So, when you said Next Door, which is restricted by geography but not by grouping, like interest groups—parents are like a specific kind of interest group—I wonder how that compares to closed spaces like Facebook that might [include] the random guy down the street, but it’s your local school system. Just wondering if that’s something you’ve done.

Thorson: Yeah, I mean, that’s just a great example. What does that mean about our future’s democratic citizens, right? I mean, there’s an old line of research studying, like, civics without—you know, civics in schools has always been the same way, right?

Let’s keep politics out and just talk about ways that we can engage. Second thing I want to pull out of that, is that super tight relationship between people saying stuff and comments, and it is going right into sort of the government processes. We’ve seen that too. We’ve seen local governments printing out Facebook comments and bringing them as evidence of, you know, what the people think. I think all of these are very different phenomena to what we’re used to, and they represent public opinion in different ways.

We’re used to, you know, which voices get heard. I mean, there is something, if you are actively commenting on local government Facebook posts, let’s face it, you are not a “regular person”—that’s a fairly special kind of focus. I think these are great questions and ones we don’t know the answer to.

Gibson: Yeah, it strikes me that for some people, their existence is politics, right? And so, just talking about issues that affect certain people in local communities becomes political.

I wonder how Facebook or even Instagram—Instagram has this new rule where you have to opt in to political messaging. So, if you don’t opt in, the feed is not giving you any more politics, right? I’m super interested to see how they determine what is political and whether that even differs from place to place. Like, is there any consideration of local community when you’re talking about what is political?

Laas: Thank you. Actually, in the subject of local institutions like that, how are changes in the structure of local news and information systems? You’ve touched some of it, but I’d love to hear the panelists kind of dig in a little more.

How are these changes in the structure of local news and information systems undermining trust in other community institutions? And Patricia, you had some Wi-Fi issues. But she’s pushing through, so if you want to lead us off on that.

Posey: Funny talking about the structure of information systems and my Wi-Fi is down. That’s funny.

I think one thing that’s interesting about this conversation that keeps coming out, or a theme across all these comments, is: what is useful information and good information? How did individuals consume this information, and where can they get it from? As Amelia and Lourdes noted two questions ago, there’s so many changes to the local information landscape. And, you know, individuals can either opt [in or] out, and they’re kind of looking for other reasonable sources and end up having all these different types of consequences.

We may see people move to other types of platforms. Or, what I think is kind of important, is what happens when people just think about what’s happening in their own community, whether visually with physical storefronts or when they’re walking through a neighborhood. I think it’s really important to note that, even in non-pandemic times. Often, we think of kind of new services or new sources—you know, places that are small, wealthy, and least ethnically diverse often had more journalism for it. Then, in larger, lower-income [communities], others have also noted that this decline in newspaper has widened the gap between high and low income. Due to different types of market sensors, [platforms] eliminate new services that kind of focus on really specific experiences that individuals end up having.

And so, you know, I’m not the first to say that, but researchers and analysts have had a long time to identify these consistent content gaps and barriers to the types of information people had, but they paid less attention to kind of the characteristic of the neighborhood. That’s where my work comes in: resident access to information and financial institution and, you know, critical information about our day-to-day finance. I need to know where it is just as much as, you know, the average paper or the average person. So, although there’s so many dimensions of how neighborhoods vary by race and income, the media has shown that these aspects of finance have always been overlooked.

One thing is I focused on in this article was asking this question of what we can learn about information inequality by focusing on the availability of new sources and financial services, in the context [of] the decline of local journalism [and how] these different types of struggling communities?” And one thing that ends up affecting this dynamic is trust. As Americans’ trust in media has declined over the years, their confidence in the mainstream banks has also found a [similar] decline, plummeting by half. Where [we] have all the alternatives to traditional media, which may include social media, Facebook news, or hashtags, you end up having all these alternatives to traditional banking as well. And so, in my work, I focus on this increase in alternative types of access, such as payday loans, title loans. In some ways, this focus may seem a little misplaced in the volume, if you don’t think about neighborhood as an important intervention in this question of changes in the information structure and changes in information. [But] part of what I’m arguing is that financial institutions, the news providers, have outlined the way we see this, and [I’m] showing the parallels of these different [ways] of being left out of traditional information.

Laas: Does anyone have any follow-up to that or questions?

Thorson: I guess I just want to add that I think your work is so important in this space, because we’ve been talking a lot about sort of the digital and the news, but the place itself is so critical, right? I think a lot of the papers in this volume really try to get at the contours of what you walk by on a daily basis and how that is informative of what you know about your community.

I would also add—and we try to bring this out in in our piece—what the historical trajectory is of where you come from, of the place itself. And we find, in fact, that for non-news actors, the kinds of content and information they produce really varies by how they see their own community. Does it have something to prove? Does it have a reputation that you want to overcome? And all sorts of these different characteristics.

I think thinking about how the characteristics of your community—[not just] your city but also your community, your neighborhood, what you actually see—is absolutely critical to this conversation.

Cueva Chacón: If I can also add to that: some of the spaces that are created, or the spaces that are covered by some journalists, are not only like neighborhoods—which I believe [are] very important, of course—but now there are these other spaces that sometimes we don’t think about as researchers or news providers or in general as citizens. They are transnational spaces, right?

Conecta Arizona, for example, serves the communities in Arizona and Sonora. Especially during COVID, that was very important because these two communities are very interrelated: people go visit family, go across the border on both sides to celebrate holidays. The people come here for Black Friday; people go there for other celebrations. And so, there’s these, you know, crossings. These communities during COVID, for instance, were separated forcibly because the borders were closed and they needed information about their families. Families were separated because of this, and they needed that connection. They needed to know when to come when they were going to be able to come back and where they could get services, if they weren’t in their original place on the border. And we don’t think too much about these spaces or places. These news organizations, these services, can create and can help communities like that get connected and get, you know, better informed. It’s important for us, as Patricia says, [to consider] the neighborhood, the streets that you work on, but let’s also talk about these other spaces that are sometimes just national—or trans-border, if you want—that we don’t necessarily think about.

Laas: Thank you. Again, I think keeping on this theme of place, Amelia, I’d like to know if you could kind of answer and think about this question with us. How can we learn or think about community-centered information needs from the perspectives of these communities themselves?

Gibson: Oh, yes, okay. So, I’m thinking on what Lourdes was talking about: the importance of place—not just transnational communities, but also sort of social structures, different social structures within the same communities. I remember having a conversation with a group of people who were talking about when their workplace would open up, their organization would open up, and there was frustration among the Black and Latina faculty in this place. It wasn’t my institution, but this other institution.

They said that it was like their admin didn’t realize that, for them, there was much more intergenerational living in households. They were going to churches with people who were at high risk. I mean, they were not the same class lines in their other social spaces outside of work—I guess, if you call work a social space, right? They were coming into greater contact with people who were, one, more vulnerable to COVID but then, two, more likely to transmit, and so there was just a lot more. The two different cultures, that crossing [of] social boundaries and social spaces, gatherings and things like that, meant that there were two different levels of risk. There were two different impacts on these two different communities that share the same space in the same community. When you go to work with your white coworkers, you are in the same space [and] you live in the same town, but if you live with your grandmother—or, you know, if you live in an intergenerational household or multi-generational household—you have different interactions than your coworkers who live just with their nuclear family.

So, there’s a lot there. I heard a lot of frustration, not just in that space but also parent spaces, about a lack of understanding outside of the institutional context of what people’s lives were like. What that tells me is that one thing that we really do need to do, when we’re looking at the impact of any information or system, is to remove the institution from the center of our inquiry. We might start with the institution and see who the people are that work, who are actors, and understand what identities and what roles they represent. Remove ourselves or the institution from the center, and then focus on them, right?

Often, there are all of these practices and cultural things that can inform the way that we understand information means and information practices and information behavior. Then it becomes not about media. It’s not about how you consume media; it’s about how you find information about your health, right? When we ask people those questions, we find they find it most by asking other people. We’ve always found most people find information about our health by asking other people. Social media might be one medium for doing that. A news organization might be one source of information that you get that information from, but even they use different media to get the information to you. I find that when we can do that, when we can remove ourselves—institutions and organizations—from the center, we can do a much better job of understanding how people seek information and how we can help them get to the information. That’s my starter response.

Laas: Does anyone else have thoughts?

Thorson: I just totally agree.

Cueva Chacón: It’s difficult, from the point of view of a journalist, to accept that, but it’s—yeah, I agree as well.

Gibson: So, I always claim librarianship—I’m a trained librarian. And it’s difficult for libraries to take themselves out of the middle of the idea of community, communities having access to information, public information, but everyone knows that not everyone goes to the library. If you’re gonna do things that are beneficial for our community, you have to kind of decenter your institution and understand how people actually engage with information beyond your institution.

Posey: Yeah, I totally agree as well, given my own personal focus on the importance of the neighborhood in thinking about this neighborhood-based information. How can it be more accessible? How can people have access to it? What can it look like? And it can’t just be centered in an institution. Although institutions are fantastic ways to get to garner this information and centralize it [through] fact check, as others have noted at the very beginning, there is a [need to] think through what it means for individuals’ source of information to come outside of traditional institutions.

Laas: So, you know, one of the fantastic parts of this ANNALS special issue is that it’s got a real clear link to policy recommendations. I’d love to maybe have all the panelists answer this question, starting with Lourdes: what do policymakers need to know when thinking about community information needs?

Cueva Chacón: It’s a big question, but again, I’m focusing on the Spanish and Spanish speakers, the Latinx-oriented or Latin population. And I think it’s important to understand that, you know, getting them information, in their language and by trusted people, is very important. For instance, I’m very happy to see here in California that the state is investing this big grant in this program called Trusted Messengers. They are putting money where their mouth is, and they are reaching out to different organizations so they can deliver important messages to their communities, right? And so, I think it is vital that you make sure that the people who are going to be delivering the information to access services that are very important, are trusted [and] trained. They don’t have to be journalists, but if they partner with journalists, that makes it even better.

The other thing that is happening here in California [Local News Fellowship] is that there’s also grant money invested in local news and training and placing young journalists in small local newsrooms. I think that is also very valuable, because then they are supporting the work that these organizations do in different languages and that serves different and minoritized communities.

Gibson: It’s easy to base public policy and whether we’re talking about health policy, public health policy, or other kinds of policy on national and state level, even state level information, but these kinds of like averages that flatten community level needs or that dismiss the like intersections of risk that people undergo force people to compensate in their information practices. So, they create these information ecosystems within their local information ecosystems.

They compensate in ways that we don’t necessarily want to see and not to dictate how people should do things. But if we’re gonna label “infodemics” a thing—if we’re gonna talk about how we don’t want people doing this and that with information around, especially COVID—we also have to consider that we’ve created a system in which they have to do that. They don’t have a good choice. They have to do that to survive. And so, being mindful of the people who need the information the most, as opposed to the most easily represented representative group, is important.

Posey: Yeah, I would add that I have no clear recommendations for policymakers, because these things are really, really complicated and what policy can look like to specifically address all the different types of issues that we outline could vary widely. But, the one thing that I think is super important, as individuals moving forward, is picking up that comment about thinking carefully about what kind of information is most important.

Can individuals get this information? How easily accessible is this information? When I say “easily accessible,” does it take a lot of time? Does it take a lot of money, a lot of energy, to get access to this information? And if we don’t have answers to those kinds of questions, fundamentally, it’s hard to [determine] the kinds of intervention that can be proposed. And so, that’s kind of where I would end, by just kind of answering these broad questions about what information matters and whom it matters to.

Thorson: Yeah, and I agree with everything that was mentioned by the other panelists. I will add two things. One, if we think that when local news goes away, that will be okay because we have digital platforms and we have all these other wonderful institutions in our communities—that would be wrong. We should not think that. And we certainly should not use the sort of framing of maybe fifteen years ago, the techno utopianism about how platforms could work, as an excuse not to address the real problems that we’re having in our local, civic information infrastructures.

I think number two is really just reinforcement of what we just heard and also picking back up on Molly’s intro: which is to say, just because there’s a lot of information out there, we should not make the mistake of thinking that people find it easy to feel informed. Across studies that I do, across studies that my co-panelists have done, we see that experientially, people find this environment cacophonous, like loud, messy, confusing. It’s really hard to know who to trust and what to trust in a time when trust overall is quite low. And I think, oftentimes, we make the mistake of thinking that if we just produce more information, people will do the hard work of figuring it all out. [But] that’s just not how people work. So, I think it’s really, really important, as the other panelists have said, to sort of think about people really struggling on the ground to make sense of a lot of these complex issues.

Laas: Thank you. Yeah, so we have time for one question from the audience, and we have one from John Hernandez. It’s a multi-faceted question from him. But you know, in a nutshell, he wants to know if there’s any promising ways for newsrooms to measure success when they’re trying to get information out to communities, especially considering the kind of polarized political climate.

Cueva Chacón: If I can chime in, I guess we have to get accustomed to the idea that there’s no one way to do it. And you know, now we talk about metrics, web metrics, social media. That’s not working anymore. I think it’s not only how much you reach out to people but also, you know, what changes you see in your community, right? You know, it might get to be [that] small numbers of people are being helped in using more services [but] it’s making our lives a little bit difficult because you cannot just push a button and have an answer. But I think it’s important for journalists to understand that we have to keep following what is happening in the community and to appreciate that small changes should be part of what we count as success in terms of benefits in our communities. And it’s the same for funders, right? There’s no one answer for that.

Laas: Okay. So, I would first of all like to thank the panelists—Lourdes, Patricia, Amelia, and Kjerstin—for their very insightful talk and answers to these questions and discussion. I will say there is much more in The ANNALS volume, which is open access. You know there’s much more in there that is of great interest and practical use, so please do check it out.

I will say, also, that we’ll be posting a transcript of this conversation on SSRC channels. The website is MediaWell. We’ll make sure to get that out over social media so you can take a look and pass this conversation on to your friends, and hopefully, these ideas and this way of approaching the issue will reach a broader audience. So, again, thank you so much for your time, and thank you to the panelists. I look forward to hearing from you all soon.

Articles discussed in this webinar, all from volume 707 of The ANNALS:

- Patricia D. Posey, “Information inequality: How race and financial access reflect the information needs of lower-income individuals”

- Ava Francesca Battocchio, Kjerstin Thorson, Dian Hiaeshutter-Rice, Marisa Smith, Yingying Chen, Stephanie Edgerly, Kelley Cotter, Hyesun Choung, Chuqing Dong, Moldir Molagaliyeva, and Christopher E. Etheridge, “Who will tell the stories of health inequities? Platform challenges (and opportunities) in local civic information infrastructure”

- Lourdes M. Cueva Chacón and Jessica Retis, “¿Qué pasa with American news media? How digital-native Latinx news serves community information needs using messaging apps”

- Amelia N. Gibson, “The problem with ‘most people’: Racism and ableism in U.S. COVID-19 public health communication”