This month, we’re expanding the “Fellows’ Corner” column by welcoming a contribution by economist and AAPSS board member Michael R. Strain with coauthor Duncan Hobbs.

If you are an AAPSS Fellow or board member and would like to contribute a post for a future edition of the Dispatch, please contact Jessica Erfer.

Reemployment Bonuses: A Promising Path to Economic Recovery

Few economic questions have more policy relevance than the effect of government programs on labor supply. Some of the most heated debates in the academy and in Washington center on this relationship. Recent examples include whether large increases in states’ minimum wage or the 2021 expansion of the Child Tax Credit reduced labor supply, and whether the past half century of Earned Income Tax Credit expansions have increased it.

Another source of controversy is whether and how unemployment insurance (UI) benefits affect labor market dynamics and employment levels. Because UI benefits are only available to unemployed workers, many economists and commentators view them as “subsidizing unproductive leisure.” Indeed, many authors have found that increasing the generosity of UI benefits increases the prevalence and duration of unemployment. Chetty (2008), though, has also shown that UI benefits enable cash-strapped households to smooth consumption: This implies that increases in duration of UI benefits may enhance the well-being of households and the efficiency of the labor market as a whole. Moreover, longer unemployment spells may increase the match quality between wage earners and employers when workers return to employment.

Apart from the direct effects of UI in labor markets, it is also reasonable to be concerned about long spells of unemployment because they are associated with health problems for workers and because workers who have been unemployed for long stretches may experience discrimination in labor market reentry.

Over at least the past two decades, many in the Washington policy community have suggested that a reemployment bonus program, which would pay unemployed workers a cash subsidy when they find a new job and exit unemployment, could be more desirable than traditional UI, which pays workers only while they are unemployed. Small-scale experiments in Illinois, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington state suggested that reemployment bonuses could reduce the length of unemployment spells, benefit exhaustions, and rates of benefit receipt. But until Idaho enacted the Return to Work Bonus (RWB) program in June 2020, no U.S. state had enacted a broadly available reemployment-bonus program on a nonexperimental scale. Our recent paper studying the RWB program is, to the best of our knowledge, the first paper to study the effects of reemployment bonuses on the U.S. labor market outside an experimental setting.

Introduced on June 5, 2020, this $100 million program provided Idaho residents who became unemployed and received unemployment insurance with cash bonuses of up to $1,500—roughly five times the average Idaho weekly unemployment benefit—if they returned to work between April 20 and July 15, 2020, and if they worked at least four consecutive weeks with their previous employer or with a new employer in a job intended to last beyond four weeks. Between July 13 and August 14, 2020, employers submitted applications on behalf of employees after employees completed four weeks of work. Idaho reported distributing nearly 30,000 bonuses worth a total of over $40 million over the duration of the program.

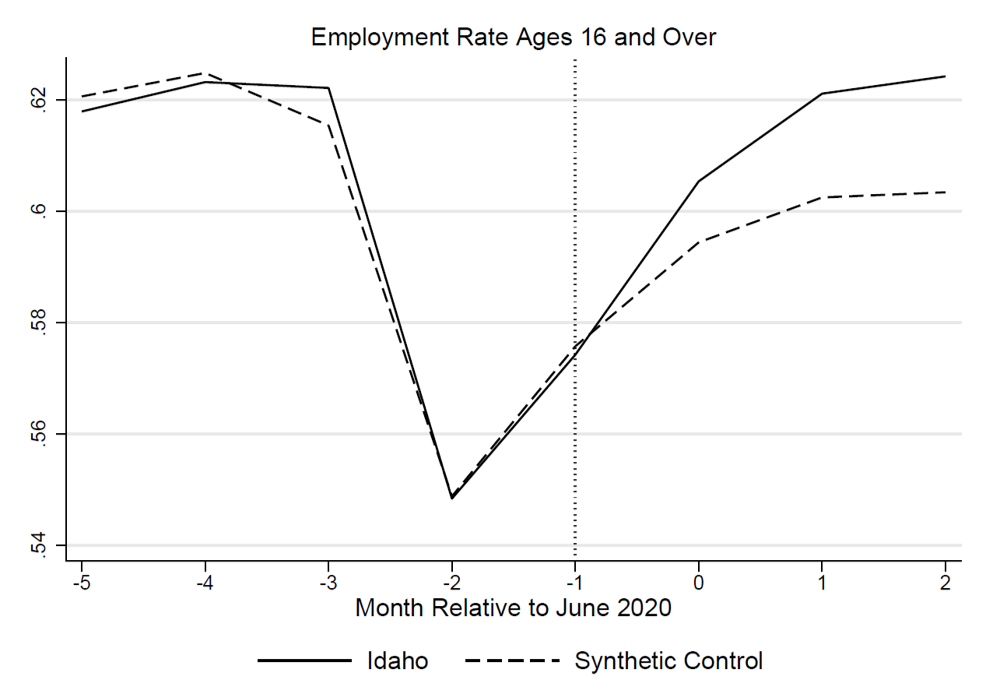

We used Current Population Survey data from January to August 2020 to estimate the effects of the Idaho RWB program on a variety of individual- and state-level labor market outcomes by comparing outcomes in Idaho from January–May 2020 (before RWB was implemented) and June–August 2020 (after RWB was implemented) to outcomes in other U.S. states where no bonus was available. We found that the Idaho RWB program substantially increased the probability of employment. We also studied labor market dynamics and found that the reemployment bonuses increased transitions from unemployment or nonparticipation into employment.

In addition to an analysis of individuals, we also studied state-level outcomes and had similar findings. Our estimates suggest that the introduction of reemployment bonuses in Idaho led to substantial increases in state employment, modest decreases in unemployment, and substantial decreases in labor force nonparticipation. Taken together, our results suggest that the Idaho RWB program substantially increased employment. The program appears to have attracted workers off the sidelines of the labor market and helped them transition from nonparticipation into employment.

To characterize the magnitude of our findings, we present our difference-in-difference estimates. (Please see the paper for our full set of results, which include event studies, synthetic control estimates, synthetic difference-in-differences estimates, and triple difference-in-difference estimates.) We estimated that, following the introduction of the RWB program, Idaho’s employment rate rose by 3.4 to 3.9 percentage points, its unemployment rate fell by 0.7 to 1.3 percentage points, and its nonparticipation rate fell by 2.4 to 3.0 percentage points. As a point of comparison, consider that in the 2001 recession the national employment-to-population ratio fell by 1.3 percentage points, the unemployment rate increased by 1.2 percentage points, and the nonparticipation rate increased by 0.5 percentage points. Given this, we conclude that, if the results from Idaho were to generalize to the economy as a whole, then they could meaningfully accelerate labor market recovery following an economic downturn.

There are many reasons to be cautious in generalizing our findings from Idaho to the nation as a whole. Still, given its success in Idaho—and the underlying reasonableness of the policy design, which attempts to advance the goal of increasing employment by subsidizing reemployment—other states and the U.S. Congress should consider enacting reemployment bonuses during the next downturn as a supplement to traditional UI, which would allow for a broader evidence base from which to assess the efficacy and effects of the policy. Governments often expand UI eligibility and generosity during recessions, and our evidence from the Idaho Return to Work Bonus program suggests reemployment bonuses are a promising tool for promoting recovery from economic downturns.

—Michael R. Strain, AAPSS board member, and Duncan Hobbs